"When my father died, (Dino Riso) told me, 'If you need another father, I'm here for you.'"

Following in their father's footsteps, Enrico and Carlo made their feature film debut in 1976 with the comedy, "Luna di miele in tre." It would be the first film in a lifelong collaboration between the siblings until Carlo's untimely death in 2018. At the heart of those collaborations was Enrico as writer and Carlo as director. The two were known for their Christmastime comedies otherwise known as Cinepanettone. Enrico has recently taken on the role of director with the 2020 "Lockdown all'italiana" and the upcoming "Tre sorelle."

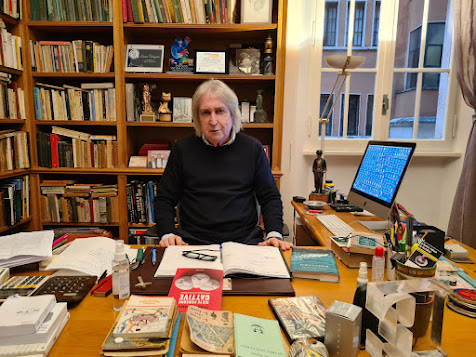

Italian Cinema Today contributor Sveva De Marinis talked with Enrico Vanzina in length about the inspiration behind his films, a few memories of the icons who shaped him, and the advice he gives young people embarking on a career in filmmaking. The original interview in Italian follows the English translation. Vanzina was so generous and eloquent with his answers, very little editing was done.

Since our readers love Rome so much, and especially the most famous locations where Italian movies were set, what does Rome represent in your movies? And how is the evolution of the city expressed in them?

My bond with the city of Rome is very similar to the one (Ennio) Flaiano had, a love/hate relationship, meaning that I always want to escape from it but as soon as I leave I want to go back. It’s a weird bond. Rome is a very particular city, probably the most beautiful; there’s a sort of “permissiveness,” which is not “absolution,” that makes living there easier than in other capital cities, everything’s easier here; you can decide to go to a restaurant or to the movies, even just a few hours before and you wouldn’t have any problems. It works like a big town but it’s the capital. It’s a topic I know very well and that I’m passionate about. For 30 years I’ve written a column about Rome for “Corriere della sera” and being the son of the director of “Un americano a Roma” (Steno), I also have kind of a responsibility towards the city. I also think that one of the most amazing shots in Italian cinema is the ending of “Guardie e ladri" after Aldo Fabrizi arrests Totò. In the end, Totò drags Fabrizi away with him. They then walk towards Saint Peter’s cathedral…it was shot in a place that, in the '50s, when the movie was made, was almost completely empty, near Via Gregorio VII, and the camera shows you Saint Peter’s cathedral, it’s beautiful. It’s one of the best shots in Italian cinema. It gives you an idea of how much Rome has changed throughout 40 years. Also in “Guardie e Ladri," there’s another important shot at the Acqua Cetosa when Aldo Fabrizi chases Totò; I’ve been doing rowing for years there, so that’s something that resonates with me.

Watch the final moments of “Guardie e ladri"..

The monumental Rome, luckily, hasn’t changed and that’s its strength. In other cities, maybe dictators and emperors called architects completely changed the face of it. In Rome, it’s not like that. Rome kept everything and that’s also why it’s so beautiful. When you walk across Rome, you can spot some ruins from the ancient times and, 100 meters ahead, you’ll see a baroque building or a medieval one or something from the Renaissance. There’s everything here. It’s like a lake in the African Savannah where all the animals go together to restore themselves at a certain time of the day. That’s what makes Rome so fascinating. It’s actually weird because, a few years ago, from a convention held by Paolo Meneghetti on the “Corriere della sera,” it came out that me and Carlo are the ones who made the most movies about Milan. We wrote a lot about Rome, though. I’ve also written with my dad, probably one of the most well known Italian movies, “Febbre da cavallo,” and the Rome we describe there consists of a lot of the historical center. We’ve told a lot, we’ve shown the most famous places of Rome, but also the relatively new areas of Rome, such as Parioli. We've also shot in the suburbs, and we’ve always payed close attention to the dialogues. Someone from Balduina (one of the quarters of Rome) will speak in a way that is different from someone who comes from San Giovanni (another quarter of Rome). We’ve always considered the sociological aspect to be very important. We were convinced that using some images of a certain part of Rome could say a lot about our characters.

Rome has changed a lot, but actually it hasn’t changed much. That’s probably because of the indolence of the administration. In the other capital cities, major public work projects were realized. Rome lacks of them; if a director wants to recreate Rome in the 1950s, he can easily do that, and that’s both good and bad because Rome will always keep that ancient atmosphere. That, for example, Milan doesn’t have. In Milan, you can easily show and represent the modern evolution. In Rome, it’s more difficult, but that’s also its charm. A big change arrived with Mussolini and the fascist architecture, like Eur, whose buildings and metaphysical structures have something De Chirico-like which was the last major public work project. Alberto Sordi, who used to live in Borgo Pio, would say that before the Fascism, to get to St. Peter’s Cathedral, you’d have to walk through a lot of little alleys and then, you’d end up in front of the Cathedral, and the feeling of amazement was similar to the one you get when you suddenly end up in Petra, in Jordan. Now we have Viale della conciliazione, which is very pretty too, but it gives away this surprise that you could get before. Same with the forum. Before, everything was a little hidden, and then you’d see the Colosseum. Nonetheless Goethe, Shelley and Stendhal, when they visited Rome had the same feeling of surprise and amazement.

|

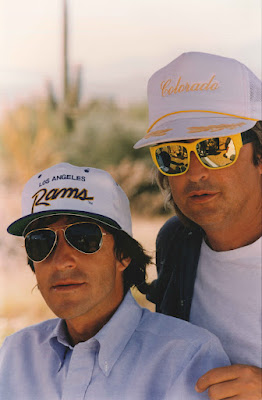

| Carlo and Enrico Vanzina on location in the US |

Of course, the one with my brother. Among the 100 movies I’ve realized, 80 of them are (in collaboration) with him. That was a collaboration of intentions, we had the same point of view on life. With him it was easy, because he used to think the same things I used to think and vice versa. I've also collaborated with many many other wonderful people. Alberto Lattuada called me when I was 25 to write a movie based on the novel by Giuseppe Berto (“Oh Serafina!”). Two monumental figures of Italian culture trusted me with their work, and for me, being so young, it was a real honor.

Another important collaboration, both on a work and a human level, was the one with Dino Risi. We made smaller movies together. When my father died, he told me, “If you need another dad, I’m here for you." That was wonderful. [I recall] his simplicity, his practical way of telling stories, his humor and also his vast knowledge.

I also worked with Lina Wertmüller and Gigi Magni. These are the people who make you understand that behind Italian comedy, there were highly intelligent and cultured individuals. People who did comedy didn’t think that it was a minor/less important genre. All the important writers I’ve worked with, the ones that did comedy, would have been able to teach college literature. The “Commedia all’italiana” was different from other genres. It could tell stories that were apparently simple but with a deeper meaning behind them. That’s why it’s different from the other comedies, both from the American one, the sophisticated comedy, and from the French one, which comes from Vaudeville. Our comedy deals with something dramatic, but it tells it in a light way, and this way, it gets deeper.

What do you think American and Italian comedy have in common?

Flaiano used to say that every drama becomes a comedy as time goes by. Because of the tone of a screenplay, even the most dramatic one, after 20 years, if it’s not a masterpiece, it becomes redundant and fake. But comedy is created with a different premise; if something is funny, it’ll always be funny, and that’s how it is also for American movies. On the other hand, the actors in American comedies are far more manufactured . But the most perfect comedy ever is “Someone Like it Hot."

Italian actors and writers work in a totally different way. American actors usually use Stanislavskij and they tend to totally become the characters they’re playing, almost forgetting about themselves. Italian actors don’t work like that. If you think about Alberto Sordi or Totò, you can see that there’s always a little bit of himself in every character he plays. Also if you think about Mastroianni, they were always themselves. In their characters, there was always some of their humanity, and that goes for French actors too, like Jean Gabin. Most of the American actors play roles, but that is not true for all of them. Some actors, that work in other genres, for example, some dramatic ones, like John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart managed to keep themselves in every character.

What's your advice to writers just starting out?

I’d tell them not to start from a script but from a topic, a subject. When you start from a subject, it has to be something that maybe you can tell in a few minutes, and most of all, it has to be something that the writer knows. He should write many things about the reality that surrounds him. When you send a bad script to a producer, if he doesn’t like it after reading 10 pages, he’ll throw it out, something that maybe you’ve spent four months on. It’ll take just a few minutes to understand if he likes a subject. You always have to start from a subject.

Among the many movies you’ve made, is there one that has a special place in your heart?

People often ask me if there was a movie I would have loved to do but never have. I’ve done so many, that I think I’ve done everything I wanted to, but there’s only one small regret. With my brother Carlo, right before he died, we wanted to make an Italian western, spaghetti western, but we couldn’t do it because right now western movies are looked at in a suspicious way. We would have loved to make it with some Italian dramatic actors. It would have been interesting, but I don’t think I’ll do it in the future.

For what concerns the movies I made, I’m like a dad with many children, and it’s often easier to get attached to the less successful ones. Among the most successful ones, I’d say “Sapore di mare” because thanks to it, we understood what we would have done next: ensemble movies where we mix humor and emotions. Among the least successful ones, “Il cielo in una stanza,” the first movie Elio Germano starred in. The plot was amazing, it would have been loved in the US. The other actor was Gabriele Mainetti, who is now a director. That movie is precious, a movie that is set in the past but in the present too. It wasn’t a huge success but I think it’s the most emblematic to understand what I would have done later in my career.

Who or what do you admire the most in the American cinema?

I consider American cinema, “THE” cinema. The US has created the best of the new craft of cinema that had just been created. I’m a huge American cinema lover. John Ford used to say that American cinema was Western above all because it was the genre that suited the American way of thinking, which is always moving, and always discovering new lands.

I think that “Stagecoach” is the best movie of all time. I’ve shot many many films in the US. I love it there. When I was shooting a movie in Monument Valley, one day, we had to shoot a scene at dawn with many Navajo extras. On that occasion, I gifted myself by paying 100 dollars to a native to let me ride a horse, which is something I’m passionate about. I rode into the desert, to the dawn. It was one of the best moments of my life.

Carlo and I also did another movie (in the US), a generational comedy called, “Mai Stati Uniti." We shot a scene at Mount Rushmore because one of our favorite movies is “Death by Northwest." We are famous for our comedies but we’ve also realized some genre movies. For example, one of the most famous Italian thrillers, “Sotto il vestito niente,” is totally inspired by Brian De Palma’s work.

If you’d have to describe with one adjective your screenwriting style, which one would you use?

I’ve always tried to keep in mind the greatest masters of the cinematic craft, Billy Wilder, but also Hitchcock, and in Italy, the greatest of the Italian comedy like Age & Scarpelli. These are all directors and authors that have the ability to observe reality and talk about it with great simplicity. Another important thing that I got from them is the use of music. Cinema puts together music and images, and it’s crucial, as Dino Risi taught me. If you use the music in the right way, you immediately give your film context. Everything that you can tell with images, is better than to tell it with words. I don’t like “nervous” movies, I like movies where you can use less dialogue, and that’s basically the same thing that happened with silent movies. Movies are movement. Everything that you can tell with images is better than telling it with words. The number one rule is simplicity, and the other one is not to be judgmental. Italian comedy has always respected everyone’s reasons without completely absolving them. We shouldn’t do moralistic and manichean movies. Movies have to tell what life is really about, and in the end, life is its own judge.

Intervista, Versione Italiana..

Visto che i nostri lettori sono molto affezionati a Roma e soprattutto alla Roma dove sono stati girati alcuni film storici del cinema italiano, cosa rappresenta Roma nei suoi film e, inoltre, l’evoluzione della città ha avuto una corrispondenza nel suo modo di fare film?

Allora, io sono legato a Roma da un rapporto come quello di Flaiano, un po’ amore e odio, passo la mia vita con l’idea di scappare da questa città, ma appena me ne vado non vedo l’ora di tornare. C’è questo rapporto strano perché Roma è una città particolare, la più bella del mondo. C’è questo permissivismo, che non è assoluzione, un modo di vivere che rende la vita migliore che in altre città. Una modalità in cui è tutto facile, a New York se vuoi andare in un ristorante, a teatro devi prenotare molto prima. Qui all’ultimo momento decidi di andare a un teatro, a un ristorante, puoi farlo. È una grande città di provincia me in realtà è una capitale. Stabilito questo rapporto, io ho dei fondamentali all’inizio al riguardo. Da 30 anni ho una rubrica su Roma sul “Corriere della sera”. Quindi è un argomento che conosco molto bene e che mi appassiona. Ovviamente essendo il figlio del regista di “Un Americano a Roma” ho anche una certa responsabilità. Io penso che una delle più belle inquadrature del cinema italiano sia il finale di un film di mio padre e Mario Monicelli, “Guardie e ladri” quando Totò viene arrestato da Fabrizi che lo porta in carcere, alla fine Fabrizi vorrebbe non portarlo più ed è Totò che lo tira, meravigliosa. Questa scena è girata in un posto che all’epoca, negli anni 50, era straordinariamente vuoto, la zona dove ora è stato costruito tutto il complesso di Gregorio VII, e sullo sfondo si vede San Pietro. Quello dà l’idea di come in 40 anni questa città è veramente cambiata. Sempre in “Guardie e ladri”, l’inseguimento all’Acqua Cetosa tra Totò e Fabrizi, si fermano, si parlano, ricominciano a inseguirsi. Tutta quella scena è girata dove adesso io faccio canottaggio da tanti anni, tutta la zona sportiva dell’acqua certosa. Sono cose che mi colpiscono molto. La Roma monumentale, per fortuna non è cambiata, questa è la forza di Roma. Roma è la città più bella del mondo, perché nelle altre città di solito arriva un dittatore/un imperatore con un architetto che rifa tutto e butta giù la città. Roma invece, per indolenza, per intelligenza, ha mantenuto tutto. Nel giro di 500 m trovi una cosa dell’antica Roma, una cosa del medioevo, una cosa rinascimentale, una cosa barocca, una cosa del 700, fino all’architettura fascista. È come un lago della savana, in Africa dove tutti gli animali vanno a bere, stanno tutti uno vicino all’altro, a una certa ora del giorno. Questo rende Roma così affascinante. Da un convegno fatto da Carlo Meneghetti sul Corriere della Sera, è emerso che io e Carlo siamo state le persone che hanno fatto il maggior numero di film su Milano. Perché abbiamo fatto metà dei nostri film su Milano, poi in giro per il mondo e poi molti a Roma. Di Roma abbiamo raccontato tantissime cose. Inoltre io sono anche l’autore insieme a mio padre di uno dei film più conosciuti su Roma “Febbre da cavallo” , dove però c’è una Roma molto “centro referenziale”, si riferisce molto al centro. Noi abbiamo raccontato un po’ tutto, alcuni film, nella Roma di sempre, quella di Gigi Magni, Piazza Farnese, Piazza di Spagna, Via Giulia, la Roma più famosa. Ma abbiamo anche frequentato i quartieri della nuova Roma, della borghesia arrembante, Parioli, Fleming, Vigna Clara poi abbiamo fatto diverse scene in periferia, abbiamo sempre avuto una grande attenzione su Roma, avendo questa grande tradizione alle spalle. Noi addirittura sul dialogo facciamo una differenza. Se una persona è di Balduina parlerà diversamente da una di San Giovanni. Tutte le volte che c’è una scena su Roma, è significativa dal punto di vista sociologico, abbiamo sempre pensato che attraverso le immagini di una certa Roma si poteva caratterizzare molto dei personaggi. La città è molto cambiata ma è cambiata poco, in realtà, per indolenza. Non ci sono state delle opere tali da stravolgere la città, se si pensa a Londra, Parigi, invece Roma è rimasta orfana di grandi opere pubbliche. Se si vuole rifare una Roma degli anni 50, la si può ricreare perfettamente anche oggi, non ci sono tante cose che hanno stravolto la città, lo skyline, è stato fatto molto poco. Pregio e difetto, perché d’altra parte a Roma rimarrà sempre quella patina un po’ antica, che poi è il suo fascino, che per esempio non c’è a Milano dove invece puoi raccontare l’evoluzione moderna; a Roma è difficile.

A proposito di questo, a un certo punto c’è una frattura con Mussolini, che introduce nel cuore della città alcune opere, architettura anche bella, al di là dell’ideologia. L’Eur è molto bello, ed è l’ultima opera di grande infrastruttura. Però il tutto ha creato anche dei problemi. Alberto Sordi raccontava che, era nato a Borgo Pio, vicino San Pietro, per arrivarci, prima del fascismo, si facevano delle stradine, e, poi di colpo, ti trovavi davanti San Pietro, un effetto straordinario, effetto come Petra in Giordania. Ora anche è molto bello con Viale della Conciliazione, ma rompe questo effetto di incantesimo che c’era prima. Stesso discorso per i Fori. Prima era tutto nascosto e poi arrivavi al Colosseo. È un po’ cambiato tutto. Il lato metafisico, De Chirichiano dell’architettura fascista, ha un suo fascino. Goethe, Shelley, Stendhal, i grandi viaggiatori, ebbero la stessa impressione di meraviglia. Oggi tutte queste cose le vedi da lontano.

Lei è un monumento del cinema italiano, e ha lavorato con i più grandi del cinema italiano. Qual è la collaborazione che l’ha toccata di più?

Naturalmente quella con mio fratello, abbiamo fatto 80 film insieme, dei più di 100 che ho fatto io. È chiaro che quella era una collaborazione di intenti, una visione del mondo identica, anche come scelta stilistica. Indubbiamente con Carlo è stato qualcosa di semplice, perché quello che pensavo io, lo pensava lui e viceversa. Con altre persone ho avuto delle collaborazioni meravigliose, però. Ricordo il primo film che ho scritto, fu proprio Alberto Lattuada che mi chiamò per un film, sua opera prima, per un film tratto da un romanzo di Giuseppe Berto. Io a 25 anni fui chiamato per scrivere insieme a loro. Questa è una cosa che non dimentico, la generosità di due monumenti assoluti della cultura italiana, che si affidarono alla collaborazione di un ragazzo di 25 anni, fu una cosa molto importante. Poi ho dei ricordi meravigliosi, di Dino Risi, anche se ho fatto dei film minori con lui. È stata un’altra persona centrale nella mia vita, anche umanamente; quando morì mio padre, in chiesa mi disse “ se hai bisogno di un secondo papà io ci sono”, una cosa meravigliosa. La sua semplicità, il suo modo concreto di raccontare le cose, il suo umorismo ma anche la sua grande cultura. Poi ho lavorato con la Wertmuller, con Gigi Magni, tutti registi che ti fanno capire che dietro la commedia all’italiana c’erano persone di un’intelligenza e di una cultura superiore, oggi questo si è dimenticato. Chi faceva la commedia non pensava che fosse un genere minore, tutti i grandi scrittori, con cui ho anche collaborato, quelli che facevano la commedia, tutti i grandi eroi della scrittura del grande cinema italiano, erano persone che avrebbero potuto insegnare letteratura all’università. C’era questo rapporto con la cultura, che veniva presa con molta leggerezza; raccontare delle storie apparentemente leggere ma con un significato profondo. Anche perché la commedia all’italiana è diversa dalle altre, da quella Americana, la sophisticated comedy, da quella francese che viene dal vaudeville. La nostra tratta un argomento drammatico raccontandolo in maniera leggera, in cui quindi la profondità è maggiore.

A proposito di questo, cosa pensa che abbiano in comune la commedia italiana e quella americana?

Flaiano diceva che col tempo quasi tutti i film drammatici si avviano a diventare comici. Effettivamente, un film drammatico che non è un capolavoro, per una questione di tono, a distanza di 20 anni diventa ridondante oppure falso, invece la commedia parte da un presupposto incredibile : se una cosa fa ridere, fa ridere, e fa ridere sempre. I piccoli film di Stanlio e Olio fanno ridere ma come faceva ridere Totò. Totò faceva ridere negli anni 50 e fa ridere ancora oggi i ragazzi. Stesso discorso per il cinema americano. La commedia americana ha un tasso di costruzione sugli attori molto forte, nonostante il frutto della commedia più perfetta di tutti è “A qualcuno piace caldo”.

Nei film italiani gli attori e gli autori usano un sistema completamente diverso. Gli attori americani usano metodi, tipo stanislavskij, che li porta a entrare totalmente nel personaggio, quasi dimenticandosi di loro stessi. Gli attori italiani no. Se si pensa per esempio a Sordi o a Totò, c’è sempre un po’ di loro, della loro umanità in tutto quello che fanno. Facevano tantissimi personaggi ma erano sempre loro, anche Mastroianni, o in Francia, Jean Gabin. Quindi, rimanendo loro stessi, portano un tasso di umanità personale molto forte. Ci sono anche degli attori americani comici che sono dei geni assoluti, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, però fanno dei ruoli, è diverso. Non tutti però. In America questo è successo con attori di altri generi, magari drammatici, hanno mantenuto loro stessi nei personaggi, per esempio John Wayne, Humpfrey Bogart, ma comunque non sono molti.

Se lei dovesse dare un consiglio a un giovane sceneggiatore, qual è la prima cosa che gli direbbe?

Gli direi di non partire dalla sceneggiatura ma dal soggetto.

Quando si parte dal soggetto, deve essere una cosa che magari si racconta in pochissimi secondi, deve raccontare qualcosa che lui conosce. Scrivere tanti soggetti di cose che lui conosce guardando la realtà che lo circonda. Quando tu mandi una brutta sceneggiatura a un produttore, una cosa su cui hai perso 4 mesi, dopo 10 pagine la butta; se invece il soggetto gli piace in tre secondi lo capisce e lo chiama e glielo dice che lo compra. A quel punto lui rimane attaccato a quel soggetto, inizierà a lavorare con altri sceneggiatori più esperti, da cui lui imparerà molto scrivendo insieme a loro. Ma bisogna partire dal soggetto.

Tra i moltissimi film che ha realizzato, ce n’è uno a cui è particolarmente affezionato?

Spesso mi chiedono se c’è un film che avrei voluto fare e che non ho fatto. Io ne ho fatti così tanti che grosso modo quello che avrei voluto fare l’ho fatto, e spero di continuare a farne ancora un po’. C’è solo un piccolo rimpianto; con mio fratello avremmo voluto rifare, prima che lui morisse, un western all’italiana, uno spaghetti western. Però non ci siamo riusciti perchè il western in questo momento viene visto con sospetto da tutti, però secondo me era una grande idea. Usare degli attori, anche drammatici, del cinema italiano per uno spaghetti western. Quello forse è l’unico rimpianto che ho, e non credo che potrò farlo in futuro.

Tra i tanti film che ho fatto, sono come un padre che ha tanti figli. Spesso quindi si vuol bene a dei film che sono stati meno fortunati. Tra quelli più fortunati, quello che mi ha cambiato la vita è stato “Sapore di mare”. Con quel film io e Carlo abbiamo preso consapevolezza di quello che avremmo fatto dopo, film corali in cui mischiare sentimento e umorismo. È stato un film molto importante.

Tra i film meno fortunati, quello che per me rappresenta ciò che io considero il cinema di commedia in Italia è “Il cielo in una stanza”, film di debutto di Elio Germano. Aveva un soggetto straordinario che si potrebbe benissimo esportare in America. L’altro coprotagonista era Gabriele Mainetti, che adesso fa il regista (“Jeeg Robot”, “Freaks Out”). Quel film è delizioso, è il sentimento, l’umorismo, il tempo, un film ambientato nel passato e anche nel presente. Andò così così, ma secondo me è il più identificativo di quello che poi ho voluto fare nella mia carriera.

(Quando mi parla di sapore di mare, a me viene in mente questa patina di nostalgia, ma una nostalgia bella e romantica. È un film che amo particolarmente, soprattutto la scena finale.

È un film costruito sulla scena finale, è un piccolo romanzo di formazione, semplice ma con tantissima roba dentro, anche involontariamente, e magari te ne accorgi dopo.)

Chi o cosa ammira particolarmente del cinema americano?

Io considero il cinema americano “Il Cinema”. È proprio l’istruzione di un paese nuovo che ha usato e capito meglio quell’arte nuova del cinema che stava nascendo. Io sono un fan sperticato del cinema americano. Come diceva John Ford “ il cinema americano è soprattutto il western” perché è il più consono al pensiero di questo paese in movimento, che scopre territori, e penso che “Ombre rosse” sia il film più bello della storia del cinema. Io ho fatto molti film in America, mi piace moltissimo. Quando ho girato a monument valley, una mattina all’alba dovevamo girare una scena con un sacco di comparse navaho, non ho resistito ho dato 100 dollari a un indiano e galoppato su un cavallo, cosa che faccio e mi piace molto fare. Ho preso questo cavallo, all’alba, col sole che nasceva, mi sono messa a cavalcare verso ombre rosse, straordinario, uno dei momenti più belli della mia vita. E poi noi abbiamo fatto un altro film, una commedia generazionale “Mai stati uniti”, film che era un viaggio attraverso l’America. Abbiamo girato una scena al monte Rushmore perché “Intrigo internazionale” è uno dei film che io e Carlo amavamo di più. L’America ci ha portato delle suggestioni e ci ha aiutato per moltissimi film che abbiamo fatto. Noi siamo famosi per la commedia però abbiamo fatto molti film di genere, ma uno dei film thriller più famosi in Italia, uno degli ultimi più venduti al mondo, “Sotto il vestito niente”, ed è un film totalmente ispirato a Brian De Palma. Per cui noi siamo sempre stati molto influenzati dal cinema americano.

Per finire, le chiedo: se lei dovesse descrivere con un aggettivo il suo stile di scrittura cinematografica, quale userebbe?

Ho cercato di tenere sempre a mente i grandi maestri, per esempio Billy Wilder, Hitchcok, e in Italia i grandi della grande commedia all’italiana, Age & Scarpelli e sono tutti registi e autori che hanno la capacità di osservare la realtà e raccontarla con grande semplicità e con un altro grande punto, che purtroppo spesso viene dimenticato: il cinema è qualcosa che non prescinde dalla musica, che invece è fondamentale. Questo me l’ha insegnato Dino Risi. Quando tu usi la musica in modo giusto contestualizzi il film subito. Tutto quello che si può raccontare con le immagini è meglio raccontarlo così piuttosto che a parole, a me non piacciono i film nervosi, mi piacciono i film dove puoi evitare il dialogo, pensa al cinema muto, il cinema è movimento, tutto ciò che si può raccontare con le immagini è meglio. La regola numero uno è la semplicità, e la seconda cosa è non avere moralismi, in un film non bisogna mai dire questo è buono questo è cattivo. La commedia all’italiana ha sempre rispettato, senza mai assolverla, la ragione degli altri, non bisogna fare dei film manichei moralisti. Bisogna fare dei film che raccontano com’è la vita film e, alla fine, la vita si giudica da sola.

Comments

Post a Comment